First Prize, Nonfiction

Jasmine Toledo Education and History, Brooklyn College

Documenting the Undocumented Worker:Case Studies in the Latin@ Experience

We the People—Defend Dignity Artist: Shepard Fairey; Photographer: Arlene Mejorado

We the People—Defend Dignity Artist: Shepard Fairey; Photographer: Arlene Mejorado

Introduction

New York City’s workforce includes members of the hardest working people in the nation: immigrants. These people come from many different parts of the world, leaving behind families, communities, and even bits of their culture in the hope of receiving financial security and a safety net that their former countries could not provide. According to the Pew Research Center, of the many different people who arrive in the City from around the world, 775,000 of them are of Latin American descent.i Since the Spanish-American War of 1898, globalization and American military intervention in Latin America have “pushed out” Latin@s from their home countries. U.S.-led trade agreements, like NAFTA, for example, have helped to crumble Latin American economies. At the same time, employers seeking low-wage workers have “pulled” Latin@s into the United States. Although Latin@s and other immigrants form the heart and soul of the American economy, they are too often overworked and underpaid.

Based on interviews I conducted with five women and five men working in the service economy, my essay seeks to give a voice to undocumented Latin@ trabajadores (workers). To keep my subject’s identities confidential, I will refer to them as “subjects.” It also compares my experiences as a female, Puerto Rican childcare provider with those of undocumented service-sector workers from many Latin American countries. These men and women come from different socio-economic backgrounds. Their stories range from living in a middle-class enclave in a Chilean city to growing up on a Mexican farm without financial reserves enough to purchase a pair of shoes. My story shares many commonalities with the histories of the female trabajadoras I interviewed, for I know what it is like to work in a home under the watchful gaze of an employer. That said, I understand that I do not experience the same sorts of vulnerability and uncertainty that my undocumented sisters and brothers endure. By tracing the lives and experiences of my subjects, I highlight how the realities of life in United States collide with immigrant expectations and desires for home and community. I argue that, despite racist rhetoric stemming from Right-Wing organizations, undocumented immigrants do not come to the United States to take jobs from Americans. Nor are they dangerous members of our community who do not pay taxes. Instead, they form the backbone of the American economy, performing essential work for employers who seek to avoid paying the minimum wage and providing social security benefits to employees. Moreover, the oral histories reveal the mythological nature of the American Dream, one used by the powerful to exploit immigrants and profit from cheap labor.

When I embarked upon this research project, I quickly learned the difficulties inherent in finding undocumented Latin@ immigrants willing to speak about their experiences. I reached out to friends and family members, explaining my project and asking them to refer me to undocumented people they knew from Latin America. Most people knew at least one person from that population, but they also stressed that it might be difficult to get the person to trust me, to confide in me. Because undocumented workers live in the shadows of the United States and do not know who to trust, I found it challenging to find people willing to speak about their citizenship status to someone they did not know. Slowly, but surely, however, people offered to share their stories. Supplementing those whom family members and friends had found, I knew I also quickly discovered that I had to reach out to my own cohort of Latina nannies, the women I have long seen at bus stops picking up “their” children from school or at parks where they tend to infants and young children in carriages. Ultimately, I found these latter subjects easier to access, since they not only knew me but also appreciated that I could relate to their stories. After all, as a nanny myself, I know what it is like to be a woman of color working in New York City in the home of someone more affluent than myself. I also know what it is like to clean up after someone else, and to raise their children. As a result, the nannies I know from bus stops and parks wanted to talk to me, to share their stories of struggle, perhaps for the first time, in a space where I could hear their voices and learn from their struggles. After I interviewed the first nanny in this cohort, word spread quickly, creating a chain effect. Over time, more women, and then men began to contact me, and to refer others who wanted to have their voices heard. As a result, I met people working throughout the shadow economy, from construction workers, cooks and waiters to nannies, housekeepers and organizers. And together, their interviews allowed me to gain an appreciation for how much undocumented workers want and need to have their stories told.

Although I have worked as a nanny for many years, nothing in my own experiences prepared me for what I heard and learned from those I interviewed. Originally, I thought I would know their stories because I have lived them as a Latina and have read about immigrant struggles. I was wrong. I found it was heart wrenching to listen to the breaking voices of grown men as they told their stories of crossing multiple border, traveling without water or food, to acquire a better life in the United States, or to witness the eyes of women young and old fill up with tears as they described leaving their families only to find themselves working in slave-like conditions in the United States. I left every interview feeling a sense of responsibility, not only to make their stories heard but to urge those within the undocumented population as well as others to organize and fight for the rights of these vulnerable people.

Our current social climate in the United States makes this work even more significant than when I began the project just one year ago. Since Donald Trump took office as President of the United States on January 20, 2017, he has waged a campaign of violence against undocumented workers, promising to build a wall along the Mexican border (where walls have long existed as a show of American aggression against our NAFTA neighbors), encouraging a neo-fascist agenda, and promising to deport both undocumented as well as documented immigrants. Trump has also helped to breathe new life into the racist rhetoric of the “dangerous, job stealing immigrant.” On September 5, 2017, Trump announced the end of DACA, a program that, despite its flaws, helped many undocumented children brought to the United States at an early age to remain with their families, seek gainful employment, and attend school safely without fear of deportation. Almost 800,000 young Americans now in college and paying taxes have lost the protection promised by the Obama administration. Coming out of the shadows, immigrants provided to the federal government information about themselves. As a result, they feel betrayed. They also face, as do other undocumented workers, both deportation as well as the reality of having their families torn apart. Making matters worse, they know that many Americans do not understand what it is like to be an immigrant of color in the United States. Although New York City prides itself on being progressive and inclusive, the undocumented Latin@s I interviewed reveal that life is a constant struggle for the undocumented, even in a City that promises to protect them.

Section one of this paper will explore U.S. intervention in the Americas and the push-pull factors that prompted my interviewees to leave their homelands. Section two explores the five-year-plan and the stories of struggle in the U.S. Section three and four examines the stories of the undocumented workers I’ve interviewed, first men then women. Finally, I explore the trends that state immigrant experiences contain, followed by some of the policy changes I suggest the U.S. needs to implement to give security to undocumented workers.

The American Dream Revisited: U.S. Intervention and the Immigrant Push-Pull Factor

At home and abroad, many perceive the United States as an exceptional place, where dreams can come true for immigrants, provided they work hard and “play by the rules.” Cal Jillson has perpetuated this idea in his Pursuing the American Dream by arguing, that the United States, although imperfect, has become a much more inclusionary society overtime. Building on the work of others, Jillson additionally asserts that only in the United States can immigrants improve their socio-economic position. Jillson believes that the United States has moved toward being more open and diverse, in a genuinely competitive environment where everyone has opportunities to rise from rags to respectability, and even great riches. Such promises of economic mobility have pulled immigrants to the United States from countries all over the world; and when immigrants fail to reach their economic “dreams,” they tend to blame themselves rather than the structural forces and cultural limitations that make it increasingly difficult for people of certain racial, class, and gender backgrounds to achieve economic security never mind success.

In Domestic Disturbances, Irene Mata debunks many of the myths of the American dream as well as the traditional immigrant story. At the core of the immigrant story, Mata argues, one finds “the desire to be embraced by one’s adopted country and an emphasis on creating a better home for oneself within the borders of the ‘land of opportunity.”ii In reality, many immigrants face racial or cultural intolerance. Although the Dream promises that through hard work and perseverance, all people can achieve economic success, it denies the reality of structural racism, sexism and classism that many immigrants face. Moreover, Mata confirms that “the conventional immigrant narrative operates based on a dependence on an ideologically constructed history—a history that privileges a specific construction of the nation as a democratic and meritocratic state. Left out of this official history are the stories of struggle and oppression of those groups that remain in the periphery.”iii My interviewees reinforce the realities Mata highlights. By telling stories of struggle and oppression, we can begin to challenge the ideology at the center of the Dream and recognize the structural problems that lie deep within the United States.

Traditional Dream rhetoric also ignores the role that U.S. foreign policy, capitalism, and globalism play in Latin America and the immigrant story. Many Latin@ immigrants do not choose the U.S. but instead are “pushed” out of their country due to economic and social hardships, caused by the role the U.S. has played in foreign governments and “pulled” to the United States by employers who seek low-wage work. In Harvest of Empire, for example, Juan Gonzalez explores the history of Latin@s in the United States. His work highlights the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which unilaterally declared all of the Americas under the “protection” of the United States and off limits to European colonizers. Invoking the Monroe Doctrine from the 19th century forward, the United States has employed this protectionist rationale to intervene in the governance of the Caribbean, Mexico, and all of Latin-South America, whether economically or militarily.

The United States has been a driving factor in Latin America. Their dictorial regimes, military occupation and economic intervention has exploited the people of Latin America and pushed them to out of their homelands and go elsewhere. As Gonzalez argued that “U.S economic and political domination over Latin America has always been and continues to be the underlying reason for the massive Latin@ presence here.”iv Gonzales asserts:

If the United States is today the world’s richest nation, it is part because of the sweat and blood of the copper workers of Chile, the tin miners of Bolivia, the fruit pickers of Guatemala and Honduras, the cane cutters of Cuba, the oil workers of Venezuela and Mexico, the pharmaceutical workers of Puerto Rico, the ranch hands of Costa Rica and Argentina, the West Indians who died building the Panama Canal and the Panamanians who maintained it.

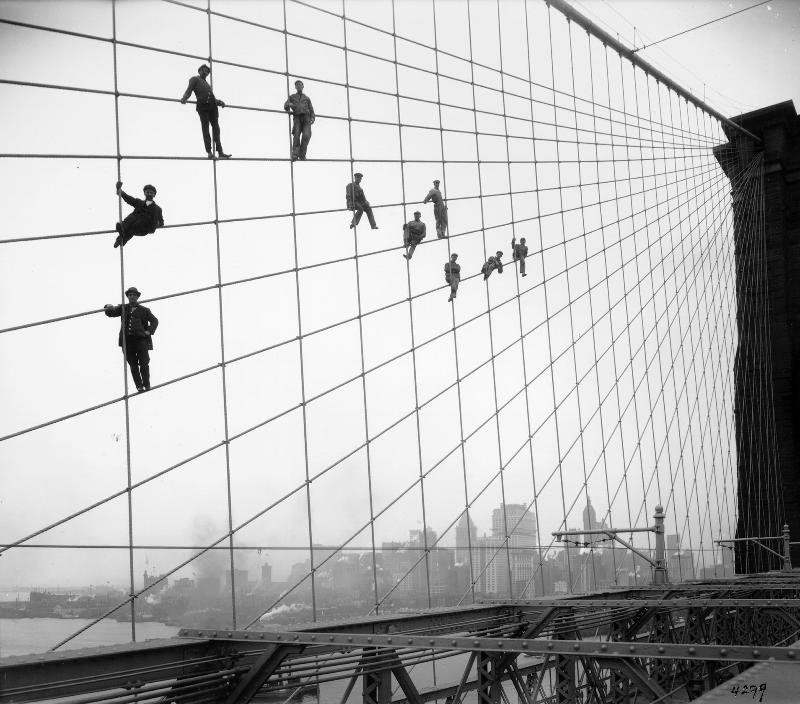

The 1898 Spanish-American War allowed the United States to gain control and colonize the subjects of Puerto Rico, which my own family was a part of. Puerto Ricans were a part of the first wave of Latin@s who migrated to the United States in the 1950s. With the expansion of sugar plantations during the 1930s and 1940s, Americans then exploited Puerto Rican workers until an expanding nationalist movement attempted to end colonialism in Puerto Rico. When the Platt Amendment passed Congress during 1903, the United States seized the opportunity to intervene in Cuba as well. This amendment allowed for the initial political intervention in Cuba which ultimately led to the Batista regime. Americans also participated in the construction of the Panama Canal to gain a foothold in Panama, Nicaragua, and other parts of Central America, with resulting military coups that allowed the United States to exploit indigenous people. The United States also made its presence felt through the installation of military bases and dictators. Guerilla wars destabilized the region, destroyed local economies, and pushed Latin Americans out of their homelands, with most of them seeking refuge in the United States.

In the Dominican Republic, the United States backed multiple dictators who supported U.S. military intervention and the whitewashing of the nation through the education system. One of the most infamous dictators of the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo was known for kidnapping and raping Dominican women. He jailed thousands who went against him and massacred eight thousand Haitians in 1937. In Nicaragua, the United States backed Anastasio Somoza García. The occupation of United States troops in Nicaragua began in the early 1900s. By 1912 the United States controlled the New National Bank of Nicaragua and the Pacific Railroad. By the mid-1900s, the United States looked forward to exploiting workers in Nicaragua, as they did in Panama, and build a Nicaraguan canal. Although it never happened, this canal is still spoken of today. Historians debate over the reason for United States intervention in the Caribbean and central America. Some argue it was due to fear that Europe would claim the territory first. Others indicate that it was for economic prosperity. Nevertheless, after the dictators of the 30s and 40s led to the anti-communist regimes against Latin America in the 50s.

For the people of Mexico, U.S. intervention started much earlier. With the secession of Mexico in 1848, the United States has kept a very close eye on our North American counterpart. There are many examples of United States intervention in Mexico but one of the most apart was the onset of the Bracero program, that lured hundreds of thousands of workers to the United States. It was brought on by Roosevelt in 1942, Mexican workers were lured to the United States for construction jobs, many of whom of stayed illegally. This brought on decades of Mexican workers coming to the United States for work not only in construction but in farms as well. This resulted in a strike at LA Casita Farms by César Chaves’s United Farm Workers Union due to the exploitation of Mexican Farm workers. With the onset of NAFTA in 1994, now, most Mexican laborers are exploited in factories.

The hundreds of thousands of workers or trabajadores who were pushed out of their homelands and pulled to the United States did not intend to stay. Their plan was to come to the U.S. to work for a short amount of time eventually return. My interviewees reflect the realities of this plan, which due to economic hardship, most do not return.

Five-Year Plan

The reality of the immigrant story is that most do not intend to stay. No matter what violence or destitution they faced in their home countries, they plan to acquire capital in the United States and then return home. One trend throughout my interviews is that these Latin@ immigrants all had a five-year plan. Year one would consist of making connections, finding a job, finding a place to live, and learning English. Year two and three would consist of working full-time job(s) in order to support themselves or members of their families all while saving and sending money back home. Year four and five would consist of saving more money and gathering things they have accumulated to take back home. They shared the idea that they would come to the United States, work hard and then take their money they had saved back home where they could then live the comfortable life they have always dreamed they could not attain. In reality, there are many things they did not consider like, getting sick, having a family, not getting the jobs they hoped to find and not being able to save money.

Most of my subjects arrived from rural parts of Latin America. They came from places where the only jobs available were farming or construction. For example, subject one is a 20-year-old male citizen of Nicaragua, where he currently resides. Nicaragua is the second poorest country in Latin America. Most people in Nicaragua work on farms or sell hand made products in the middle of the street. While I was crossing the Costa Rican/Nicaraguan border I saw this man with tattered clothes selling trinkets. I decided I would interview him. He dreams coming to the United States to make money, working in construction or anything available to him. Although he has a young daughter, he is willing to risk crossing all the borders on foot for the second time. Around 2013 he tried coming to the United States for construction work in California. On foot, he crossed all the borders of Central America very easily. Most Central Americans go from country to country daily without any problem. When he arrived in Mexico, it got a more difficult. Without any water, food or money the Mexican government deported him back to Nicaragua. He never reached the United States. He believes the United States is a land of opportunity, freedom and equity. His plans are to work for a little while and return home with enough money to live comfortably with his family in Nicaragua. This is the dream of many of my interviewees and their family members.v Many of my subject’s experience reveal the five-year plan.

Subject two is a 30-year-old Mexican nanny living in Brooklyn, New York. She was born in Guerrero, Mexico, Guerrero is a large state. Subject two is from a very small town, consisting of only three paved streets. There are few opportunities for young people, especially women. In order to go to high school, one must take a bus to the next town. Her parents brought her to Brooklyn when she was seven years old. She went to elementary school, junior high school, and high school in the United States and considers this country her home. She is also a DACA recipient. She explained to me that her family left Mexico because they heard stories about the United States and how it was easy to get a job here. When describing her family’s experience in the United States she argued, they had no long-term plan. When they arrived They wanted

A better quality of life. An easier life. They had two kids, a 3rd on the way. And just being able to survive somewhat better than they could back at home. It was just supposed to be 5 years. Just before the kids got into school so that they could go back home and start school there but 5 years turn into 6, 7, 10, 15.vi

Like the workers of the Bracero Program, subject two’s family was lured here through a work program. Her grandfather was the first person to reach the United States. An American recruit offered him a job in California. He would travel back and forth from Mexico to California every few months. He started bringing back American products that their small town has never seen before like radios, televisions and other electronics. Their family began to think the United States is very progressive, modern and a place where people can receive opportunities. Soon, more and more people in her family began coming to the United States for work.

A young man, subject three, has a similar story. He is 22 years old, born in Guatemala, and also a DACA recipient. While explaining how America was represented in Guatemala he argues, “There is this idea that the US is the land of opportunity and it has a lot to offer in terms of jobs. For my parents, it meant a better future for both their children and viives” The other trend that one can quickly see is that work is the defining factor for these immigrants. It is the underlining reason why people immigrate to the United States, it is the economic imperialism that pushes them out of their home countries. Due to the American economic intervention in Guatemala, their citizens are left destitute and in search for jobs. Like subject two, this family from Guatemala also did not intend to stay. According to subject three, his parents were building a home back in Guatemala and after the construction of the home, they would go back there to live. As time went on, the idea of going back “home” faded. They were never able to save enough money due the long work hours and inadequate pay they faced in the United States. This story represents the reality of coming to terms with the fact most immigrants can no longer return to their home country due to the new cycle of poverty they have entered in the United States. The opportunities, jobs and money they intended to acquire were non-existent. After time passes, these immigrants begin to create a life for themselves in the United States and the reality sets in that they could not save enough money to return home. This is where reality begins to collide with the American Dream.

The Realities of the Undocumented Male Worker

The men of Latin American families often travel to the United States first in hope of obtaining construction work or work in the service sector. In modern times, this has been changing, women are often becoming pioneers of immigration and coming to the United States first for search of domestic work. The plight of the undocumented male workers is hardly documented. Throughout my experience, I quickly realized male undocumented workers are more accessible. They predominantly work in the service sector and manual labor positions. They are often invisible, working in the backs of stores or blending in with other unionized workers. They do not receive the same resources as their fellow documented workers. Often, they do not receive helmets, lunch breaks or adequate pay. The men I’ve interviewed come from different parts of Latin America and have different experiences. The thing they all have in common is they were pulled to the United States to try and achieve the American dream either for themselves or their children.

Subject four is a man from Chile. He is a 62-year-old gay white Latino. Before I started turning on my recorder, he began to tell me, “you should know, my story is not the typical story of an immigrant, I am privileged.”viii I told him not to worry, everyone’s story is very different and I tried to make him feel comfortable. This subject was born in a city in Santiago, Chile. He had middle class parents, who were conservative and did not agree with his homosexuality. He had the privilege of being a tour guide in college. He used to bring students back and forth to the United States through an exchange student program. During one tour, he decided to overstay his visa and not go back to Chile. He says he was searching for freedom.

The Chilean worked many jobs but he was lucky enough to have made a lot of friends and connections on these trips. Many of his friends set him up in jobs and even provided him with a home. They helped him get a fake ID, social security number and more. He’s lived in many different states and honestly, he made it seem like he lived a fun life. He was involved in many organizations and fought for gay rights throughout his life. When I asked him if he was ever vulnerable he said no. He told me throughout his demonstrations he put himself in a position where he could have been arrested. It didn’t matter to him that he was undocumented, what mattered to him was that the government was putting through rights for the LGBTQ community.

He obtained his citizenship status through getting married to a friend and his luck persisted. His immigration interview happened to be with a Chilean man. He was granted citizenship a few days later. I asked him if he thought he would be so lucky or have a different experience if he was Afro-Latino. He told me, absolutely not, he realized that his skin color helped him as an undocumented person and his life would have played out very differently if he was an Afro-Latino. I was very glad that he recognized his privilege.

This experience is not the typical immigrant experience, although this subject suffered in various ways such as homosexual discrimination, he is financially stable. Subject five is a young man whom I’ve interviewed from Guatemala has a completely different story. He was born in Guatemala but came to the United States around five years old. He has no memory of his home country. He is a former DACA recipient. His father came here first to see what the United States is like. Although he realized he has to work harder than he expected, he believed his wife and children could make a life for themselves in the United States. They came to the U.S. with the help of coyotes. Their plan was to come for five years, save up money and buy a house. Although most people come with this plan, it doesn’t happen and it didn’t for this young man and his family.

Throughout his time in N.Y.C this young man was pushed into low paying service sector work. His typical day begins at 4 o’clock in the morning. He gets ready and leaves his house at 5. He get to work around 6. He works from 6:00–3:00 and most days, stays overtime. He argues, people basically stay until they are told to go. People do not have a choice whether if they want to stay or not. They are forced to do overtime or face being fired. His typical day is very similar to most undocumented men, most immigrant men at that. He runs on very little sleep, works very long hours and doesn’t necessarily get paid for every single hour, let alone overtime hours. He does not get paid enough and does not want to stay at his job. This young man has seen people get injured and cannot say anything because most people at this meat factory are undocumented. These workers are not in a union or don’t have health care. They are completely vulnerable. They are subjected to their employers threatening to deport them. When he first started working at this job, he didn’t even have helmets. When the first person got hurt, his boss finally gave the workers helmets because he realized these people are becoming a liability.

This young Guatemalan man soon applied for DACA. A DACA application is $480 per person. His mother and father had to scrape up money to do it for him and his two other siblings. He describes what life is like on DACA:

There is no security at all. You feel like the workforce doesn’t want you at all. You completely have to be complicit to all the rules that apply to immigrants without papers. You can’t say anything. You just have to be compliant.ix

Life on DACA is a very vulnerable life. It is an isolated life. DACA was just a band aid to a much larger issue of being undocumented.

A similar story comes from a young man interviewed from Honduras, subject six. Just like the Guatemalan, he is also 23 years old but he just came to the United States four years ago. He is still living his five year plan. He was lured to the United States by the thought of having a good, fun life. He just beginning his 20s and was looking to escape his parents household and live an independent life. His journey to the US was 2 and a half months. He came on foot, crossing border after border. He crossed with a help of a coyote whom he paid $7,000. His aunt saved up two months to help him pay for this. He was scammed by many coyotes, he wasn’t allowed to speak to his mother, he was starving and thirsty. He was so thirsty that the first time he put swallowed a piece of bread, it actually hurt. So far, his five year plan is not going as planned. He is struggling financially, just making ends meet. He is a delivery boy for a café. He doesn’t like it here, he told me he doesn’t feel free like in his country and he wouldn’t advise anyone to come here. Although he told us that his job is okay, he can’t complain. I saw it in his eyes that he is lying, he is just telling himself that. His eyes were bloodshot and glossy. This was from pure exhaustion. The heart wrenching part of his interview was that he wasn’t a 30 year old man whose been here for 10 years like the Chilean. This was a young boy who just arrived and has no idea what he got himself into. Many times it looked like he could have cried during the interview but was trying to hold it in. His story is the reality for many undocumented men.

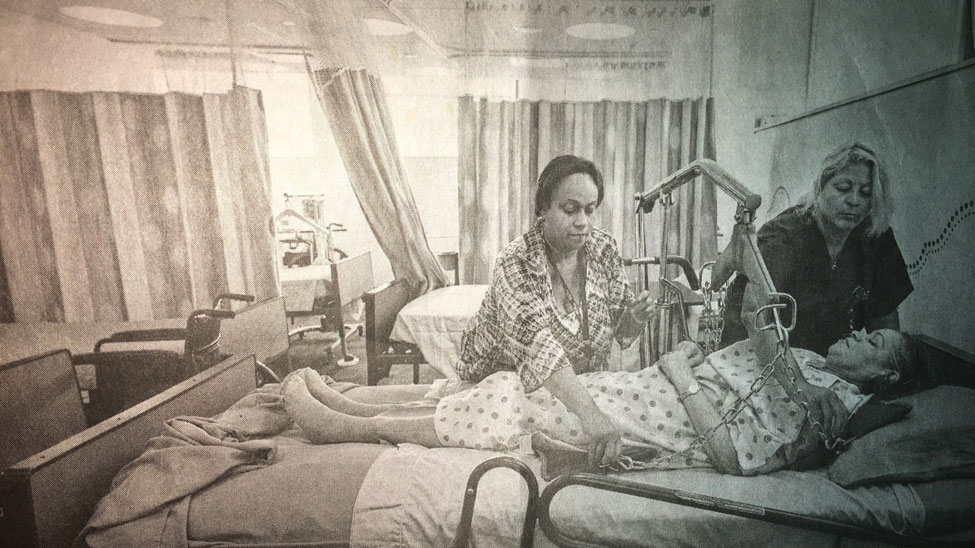

Domestic Workforce

My own story consists of being in the domestic workforce. I started getting into babysitting when I began college. I knew I needed a flexible job because of my school schedule. Since I would mostly babysit during after school hours, it seemed like a good part time job. My grandmother and her mother were also domestic workers. I never realized that working as a nanny or babysitter would be so time consuming. One is essentially responsible for raising a child that is not your own, being in someone’s home and constantly watched by your employer. Tamara Mose Brown analyzes this in her book Raising Brooklyn. She argues that, “given this form of control that providers have over their workday, parents are reduced to certain tactics in order to combat their feelings of losing ground… they may for instance, use various means of surveillance, develop new rules, or simply speak badly about childcare providers.”x Ultimately, employers want to feel like they have the upper hand and are not losing control. Because urban work gives employees a certain degree of freedom, parents may rely on nanny cams or other people in the neighborhood to let them know what their nanny is doing. Frequently, they belittle their employees or use passive-aggression to prove that—at the end of the day, they have the upper hand.

Quickly throughout my nannying career, I began to realize the domestic workforce consists mostly of women of color or women who are immigrants. We are lured into these low-wage positions by wealthy, privileged families. We are often disrespected by the children and have nowhere to complain because the children reflect our boss. Not only are domestic workers responsible for taking care of other people but also taking care of the home. People who have never worked in domestic positions do not realize that picking up after someone is mentally degrading.

Nevertheless, no matter how degrading this type of work is domestic workers fall in love with their “children” and see themselves as part of their family. Subject seven is a woman in her early 30s from Mexico who came here as a child. She is a DACA recipient and also a nanny in Park Slope, Brooklyn. She got into nannying about six years ago. She was recommended by a friend who was nannying as well. She was introduced to a woman who she came to truly admire. She went to college, has a beautiful apartment, has a husband and children and claims to live the “typical” American dream. The woman from Mexico currently takes care of a young girl and a boy who she has known since the day he was born. She is literally raising him as if she was his mother. They have a very strong bond. She argues, being a nanny is like taking care of your own kids I guess. She explains

When I started my nanny job, the baby who is now almost 4 wasn’t even born. I got raise him as my own. I taught him Spanish. I want to say he loves me; he misses me when I am not around. Sometimes, he wants to call me mom but I tell him I am not his mom, I am his babysitter.xi

As one can see, this baby is being cared for by someone who truly loves him. But, although she feels a part of their family, once the boy goes into elementary school she will be forced to find another job because they will no longer need her full time. That is the reality of these domestic work relationships, once the family no longer needs you—you are forced to fend for yourself.

Another young domestic worker whom I’ve interviewed, subject eight, is also a young woman in her early 30s from Ecuador. She is from Quito, the capitol. She grew up in the city in a working-class household. She completed high school in Ecuador. During her time in school, she was exposed to people from America who were trying to recruit young girls to come to the United States. She would see ads posted around her neighborhood and people who would talk to her on the streets about it. They told her they would take her to America, all expenses paid. It wasn’t supposed to be for work, it was supposed to be for tourism. She would be housed in a home of someone who is American. As a young girl, she was very impressed by this offer so she agreed. It was only supposed to be for a few months. Little did she know, it ended up being years. As she went on the plan to New York, she was greeted by the person whose home she was supposed to live in. She was explained what her duties would be. They were to cook, clean and take care of their children. She would be housed in a very small room. She was extremely scared, didn’t know English or have any connections. This woman was a modern-day slave. Working over 40 hours a week and being payed thirty to fifty dollars per week.

After putting up with this for months, she ended up meeting other nannies outside in parks. She managed to escape her situation by making connections with a different woman who also needed a live-in nanny. This time, she was payed adequately but still had no way of returning home to Quito. Till this day, she still has not returned home. As one can see, there is a stark contrast between this woman’s story and the Mexican woman I have described. Although some domestic workers do find a family with their employers, many do not.

Brazilian women have also economically lured to the United States. Subject nine is a white Brazilian woman in her mid-thirties. She was born in Minas Gerais, Brazil to a middle-class family. Although her family was fortunate enough to own a home in Brazil, they lived in a dangerous rural neighborhood. Her sister was the first one in her family to come to the United States in search for work. It is much easier for white Brazilians then it is for other Latin Americans. Most of them get approved for a visa on their first try. Black Brazilians claim to never get approved after multiple attempts. After subject nine’s sister came to the United States and found domestic work in queens, she decided she wanted to make the attempt as well when she turned 16. She didn’t speak English and her only contact was her sister. Luckily for her, her sister had many contacts for work. She began working as a cleaning lady for very wealthy people in Manhattan. For the most part, she claims to have been treated decently in all her positions. The people she worked for helped her learn English and referred her to other clients so she can make more money. The different between her and the other women I’ve described is her skin color. Race can be the defining factor for how women are treated in these positions.

Subject nine ended up meeting her husband through working as a cleaning lady. He is a wealthy lawyer living in Manhattan. Meeting him changed her life. He put her through school, helped her improve her English and payed for her citizenship papers. This interview was very different than any other interview I’ve done because this woman lives a very different life than the other female subjects I’ve interviewed. I traveled to one of the richest neighborhoods in Manhattan, where she currently resides. I was greeted by a doorman in fancy clothes and walked into an apartment building lobby decorated in lavish gold furniture. The inside of her apartment was spotless and the windows reached from the ceiling to the floor. Looking out her window, you can see the borough of Queens, the same place she started out as a cleaning lady when she first arrived to this country. She is the exception. She has no plans on returning to Brazil, she even told me that when she goes there for vacation she wants to return home, to the United States.

Assimilation

All the immigrants I have interviewed have been living in the United States for at least three years. The thought of returning home is a constant hope and struggle. Many of them did not intend to assimilate to American capitalism and culture but have succumbed to the American way of living. Many of them buy name brand clothes, eat fast food or are just attracted to the modern American lifestyle. Things that Americans think are simple like having a sink with running water, were once new to many of my subjects. Subject ten is a woman in her late 50s from Guerrero, Mexico. She grew up in a very small rural town on a farm. As a child, she would work the fields for a living, tending to cows, chickens, goats and other farm animals. She came to the United States in the 1980s in her early 20s. When she first arrived, she had no intention of staying in the United States for all this time. She didn’t even want to come, but her husband convinced her with the argument that her children would have a better life in New York City. Her first job was selling Mexican tamales on different corners in Brooklyn, NY. She would even bring her children with her on their summer or winter breaks. Little by little, the same woman who raved about returning to her farm, began to learn English, eat American fast food and shopping for name brand clothes. She began to assimilate, something many immigrants say they would never do, but find that in order to survive, it may be necessary.

Assimilation is an important part of the immigrant story. It is something every immigrant struggles with. Assimilation can be seen as a marker of success for the traditional immigrant. Irene Mata argues, modern immigrants are not assimilating but acculturating. This means, they do not give up their own culture but they add certain parts of American culture to their lifestyle when it benefits them. The reason for this is because modern immigrants are often immigrants of color who cannot assimilate because of their race. Most of them do not even prefer to assimilate. Many Latin@ immigrants, and other immigrants of color have created immigrant communities for themselves. Mata points out, “the immigrant communities make up a vital part of urban spaces, the new immigrants is no longer ‘the other’ but is instead just ‘one more’. It is only when the immigrant subject leaves the community of immigrants that she is confronted with being the ‘other’ but as soon as she returns to her immigrant community, she again belongs.”xii I see these “immigrant communities” all over New York City. One of the most profound immigrant community is in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Walking through the streets of Sunset Park, one feels like they are not even in Brooklyn anymore. They are suddenly in a Latin American metropolis. One can see people of all shades from tan to brown, you hear different dialects of Spanish from the Caribbean to Central America and you smell the sweet scent of tamales, tostones and arepas.

Although the assimilated or acculturated immigrant is often still marginalized in the United States, when they return home they are seen as “privileged.” The same woman I have described above does not fit in with her family members still living in Mexico. Family members of immigrants often have misconceptions of them being “rich” or living lavish lifestyles. They do not understand that they are living paycheck to paycheck. They do not understand that they are working over 40 hours just to be able to afford to send money back home. Family members of immigrants who still live in home countries often believe people who immigrate to the United States enjoy luxurious and lavish lives. They often believe that their newly “American” family members make excellent wages, live in large homes, and eat as much as they want every night. It is not their fault they believe this. The American media, and Hollywood movies, convince people from around the world that the United States is the land of opportunity, where all things are possible, where hard work leads to middle-class respectability, even riches. According to Andre Torres, “remittances of immigrant workers have replaced U.S. Foreign aid as the main external assistance for several poor countries south of our border.”xiii This is how families in home countries make ends meet. Many of my case studies reveal the realities of having to send money back “home” to a place they no longer fit in, where distant family members now see these immigrants as “privileged” When these immigrants return to their home countries, their relatives see them as wealthy. Their family members do not comprehend how much immigrants struggle in the United States and that their perceptions of the country are false.

Many family members of immigrants do not understand how much their American born family members suffer as well. Although, New York-born Latin@s do not experience the same inequities as their immigrant or undocumented parents. They do not have to “lay-low” or live life with the fear of being deported. Documented Latin@s navigate society differently. They think nothing of filling out forms, giving people their real names, or applying for a state ID. Regardless, as Torres argues, they continue to experience poverty at “double and three times the level of white New Yorkers.”xiv Indeed, members of this community, my community, are still relegated to low-wage positions, inadequate health care, and employers who profit from the vulnerability of immigrants who are often forced to divide their wages among family members in the United States and family members from whence their parents came.

New Yorkers see themselves as providing unique opportunities to immigrants in the wake of the “Latin Boom” during the 1970s. But that “Boom” took place because of US-induced turmoil in Latin America, in political crises that caused Cubans, Central Americans, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans to leave the only homes they had ever known.xv Over the past 40 years, further turmoil has consistently increased Latin American immigration, with Latin Americans now constituting 30% of New York’s post-World War II immigrant population. Torres, has noted that Puerto Ricans became the largest group of Latin@s in New York City during the 20th century; however, their numbers have begun to shrink as others arrive from different parts of the Latin@s diaspora. With Dominican and Mexican immigration on the rise, they have joined Puerto Ricans in making up 70% of New York Latin@s population.xvi Although many of these Latin@s are now New York-born, they are increasingly joined by undocumented immigrants from around the world, many of whom have fanned out to other parts of the nation. Indeed, 59% of all undocumented works now call both New York as well as California, Texas, Florida, New Jersey, and Illinois home. And like those other states, New York’s undocumented workers from Central American and Asia have increased substantially from 2009–2014.xvii All in all, these New York Born latin@s and their undocumented family members often do not find their place in society. They are not from here, nor from there. No son de aquí, ni de allá.

After the Latin Boom in the 1970s, the US experienced peak unemployment. In her article “Openings in the Wall”, political science professor, Leah Haus argued, that the economic crisis of the 1970s and 1980s changed U.S immigration policy. It began to allowed for immigration. The U.S. even enacted the Immigration Reform and Control Act which protected undocumented workers and granted amnesty for undocumented workers residing in the country since 1982. The U.S. government enacted the Immigration Act which included some restrictionist measures that made it harder to receive work permits but increased admissions for high-skilled workers.xviii Haus analyzed the periods of immigration legislation of the 1980s-90s through a state centric approach, “the societal groups that influence the formation of U.S. immigration policy contain a transnational component, which contributes to the maintenance of relatively open legislation.”xix Furthermore, she demonstrates that unions help protect foreign-born laborers from restrictionist measures.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, my interviews suggest the need for policy changes. There are many things the United States and its citizens can do to help the undocumented population and the immigrant population of the United States. One of them is to help strengthen unions. Unions and labor groups help the undocumented population to organize make it easier for them to understand their rights as workers. Unions support amnesty for undocumented workers and help them to gain legal, permanent residency. They also fight against sanctions that prohibit workers from organizing against employers. Unions and organizations give workers a voice and help ensure their protection.

Unions are important for undocumented laborers across the United States because they help ensure these workers are being paid a fair wage. The fact that many of them are undocumented produces the “desirability of Latino immigrants as laborers, through what employers perceive as vulnerability leading to a willingness to work harder and without objection as compared to native-born workers.”xx These positions include not only service sector jobs but manufacturing and domestic work as well. Essentially, the American companies thrive on cheap labor in order to profit. In the article “The Growing Force of Latino Labor” Hector Figueroa expands on Haus’ idea of unions helping undocumented Latin@ laborers. He argues

The history of Latino labor is being forged by volunteer rank and-file workers in the garment industry who have rebuilt unions. Also by the thousands of farmworkers, drywallers, janitors, hotel workers and other low-wage workers who have engaged in massive strikes, militant action and civil disobedience to bring public attention to their straggle to win dignity, higher wages and decent working conditions.xxi

Figueroa also supports Haus’ argument that there was indeed a resurgence of immigrant labor in the 1980s which was because of many international factors such as a world recession, economic difficulties in Latin America, increased trade and foreign direct investment which displaced urban and rural Latin Americans and the U.S. military intervention in Central America.xxii Figueroa argues that Latin@ immigration is the effect of many components which blended Latin America with U.S. capitalistic endeavors. It is the effect of globalization.

An important thing to note is Latin@ workers undocumented or documented are not homogenous. There are many differences between Latin Americans including “national origin, gender, race, immigration status, language, economic sector, geographic region and integration into the U.S. labor market.”xxiii Geographic and immigration differences often make it difficult for Latin@s to organize and unionize. Geographic differences matter because of the jobs that are offered to the undocumented. For those who live in regions that offer immigrants informal work arrangements, unionizing is decreasing. Immigration status matters because many Latin@s initially deem their time in the U.S. as temporary. Haus argues, unions stress restrictionist measures for these groups because they have a different societal identity, unions assume they will only work for a short period. This group is difficult to organize.xxiv Therefore, the decreasing number of Latin@s in unions depresses wages for undocumented Latin@ workers.

There is also much to do to help women in the domestic workforce. In The Age of Diginity, Ai-Jen Poo argues that due to the baby boom of 1946–1964, America is about to experience an elder bloom. Because of health care technology advancing, people are living longer than ever but they need help. She finds that by 2050 about 27 million elders will need assistance that of which is consumed by women.xxv “Many of the existing eldercare workers are low-income African American and immigrant women who are faced with innumerable challenges, among them low wages, long hours, and inadequate training.”xxvi Not only do workers need to be protected in terms of workers’ rights and training but the elders also need a better healthcare program that will keep them out of the hospital and pay for medical expenses. We need a care infrastructure. “Care is something we do; it’s something we want; it’s something we can improve. But more than anything, it’s the solution to the personal and economic challenges we face in this country. It doesn’t just heal or comfort people individually; it really is going to save us all.”xxvii

The Domestic Workers Bill of rights took effect in NY in 2010 (after a long fight). This Bill mandates eight-hour work days, overtime, a consecutive twenty-four hours of rest per week, three paid days off, protection against discrimination and harassment and a worker’s compensation insurance program.xxviii Poo argues, we must take this further: we need a Care Grid. If not, poverty will result in poor healthcare for the workers and the elders whom they care for. “The Care Grid brings together public, private and nonprofit resources and creates a comprehensive coordinated system in which elders can age with dignity and their caregivers, both professional paid workers with unpaid family or friends, can thrive as well.”,xxix The Care Grid should consist of a Social Security plan that covers not only wages but income from capital, investments, stock and rental income. Also, strengthening the programs that support Social Security like Medicare and Medicaid. These programs should have a refundable tax credit for working-age people whose incomes are too high for Medicaid but too low to afford health care. For the workers, Poo believes we must improve job quality by making sure all workers receive the benefits they need in terms of $15 minimum wage and even a health care program. Workers also need training for health care aids. Lastly and undoubtedly the most important is a citizenship program where undocumented workers can receive a path to citizenship.

An overwhelming majority of these workers are women.xxx Many labor regulations have not included protection for domestic workers like the Fair Labor Standards Act, the National Labor Relations Act and more. This is because many people do not consider nannies, babysitters and more “real jobs” or jobs that need protection and rights. As a nanny, I’ve experienced this. I’ve had one of my children who I work with ask me what I do for a living. I replied that “well I take care of you and your sister.” The child looked me right in the eye and said “no, I mean what is your real job.” One may argue, well he is just a child and doesn’t know better. At one visit to the dentist, the hygienist was trying to make small talk with me and ask me how my day was and what I do for work. I said, “I take care of children, I am a nanny.” She didn’t have the nerve to look at me when she responded but she continued working and said, “that is not a real job.” As I ponder on these moments, I think back to my trips to Latin America, where all jobs were honorable. No matter what a person did, sell tamales, fruit, take care of children –families thanked them for making money to pay for dinner and rent. In the United States, these jobs are looked down upon. In Gloria Steinem’s essay entitled “Revaluing Economics”, Steinem argued that “labor is valued in accordance with prevailing social constructs about race, sex, and class. Jobs in high finance are valued with comfortable compensation, for example, while the work of caring for people is often deemed unworthy of a minimum wage.”xxxi Sheila Bapat offers solutions that the government can do to help domestic workers such as fund immigrant community organizers and domestic workers’ groups, reform diplomatic immunity, increase visas for domestic workers, improve paid family leave policies and continue ensuring that labor law and policy includes domestic workers.

Sheila Bapat expands on Ai-Jen Poo’s book by talking about female workers in other realms of the domestic sphere such as nannies, housekeepers and caregivers in her book Part of the Family?. Bapat realizes that domestic workers are more vulnerable than any other workers because unlike other workers, they are unprotected by laws. Part of the Family? Focuses on the ways domestic workers have empowered themselves to be advocates for themselves. Bapat realizes the domestic worker’s roots in slavery and how the law has not addressed the failures of protecting the workers. She also advocates for immigration reform and unions.

All in all, my research has proven how the workforce of the United States includes members of the hardest working people in the nation: immigrants. They are the blood, sweat and tears of the economy. They are what makes it thrive. Through my interviews, my subjects have demonstrated how they come from different parts of Latin America. Parts that have been economically and socially destroyed due to United States intervention and yet, the current government has much to do in order to get closer to achieving quality for this marginalized population. Some of my subjects come from the cities of Chile and Ecuador while others come from rural parts of Brazil and Mexico. Regardless, they all share something in common: they were all pushed out of their countries due to destitution and pulled to the United States for jobs, education and safety. Through this experience, I’ve had the privilege of meeting undocumented immigrants from all walks of life. Some who are working in the service sector while others who are currently working in the domestic workforce. They did not intend to stay in the United States. They intended to work here for a period of time and return back to their native homeland. But, due to the impossibility of achieving the American Dream or economic security, they are forced to stay. The immigrants who want to stay, are those who had no say in coming to the United States: those who are on DACA. Now more than ever, unions, activists and organizations must come together to support vulnerable DACA recipients. We must continue the fight for citizenship for these young adults who were once DACA recipients and even their parents who brought them to the United States. The government must create a path to citizenship for them.

Organizers must also fight for an end to United States intervention in Latin America, including an end to the colonial regime of Puerto Rico. The United States has continued to use the rhetoric of “helping” these nations to justify the damage they have done to their economies and societies. Activists, organizers and unions must also bound together to fight for equal wages for undocumented workers, immigrants and especially, domestic workers. Currently, the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights has no protection for part time workers or a health care plan. Following Ai-Jen Poo, the United States must incorporate a Care Grid to support domestic workers.

The fight for equality does not stop here. My work focused on economic rights for the undocumented community but there is more to be done socially and politically for these vulnerable people. They depend on organizers to give them a voice when they cannot come out of the shadows. My research depicts the lives of a few case studies but these stories represent the rest of the thousands of people who are undocumented and living under the radar in the United States. Scholars need to continue helping them get their voices and needs heard. We need to give them the documentation and citizenship that they’ve long deserved and worked for. We need to continue documenting the undocumented.