First Prize, Narrative

Sean Blair Television and Radio, Brooklyn College

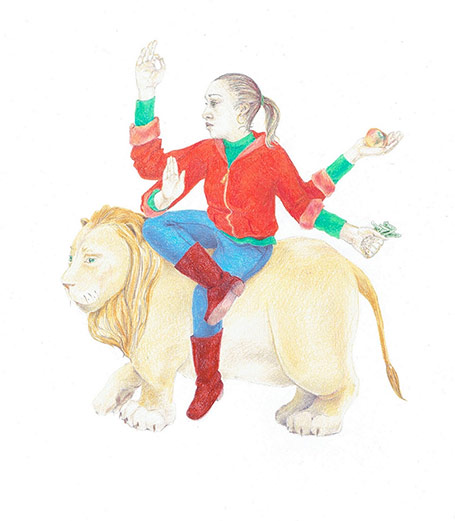

Lewis Grant & The Walburn Bros.

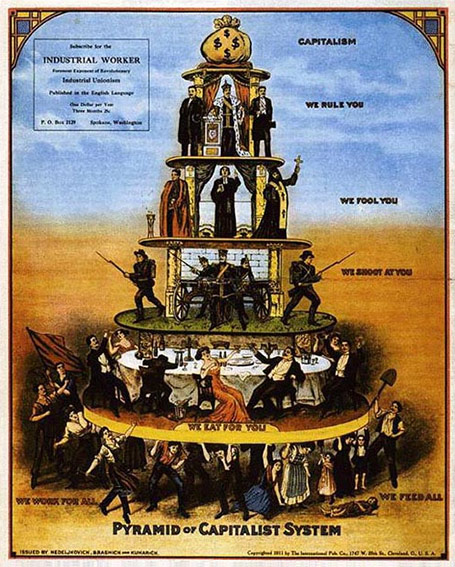

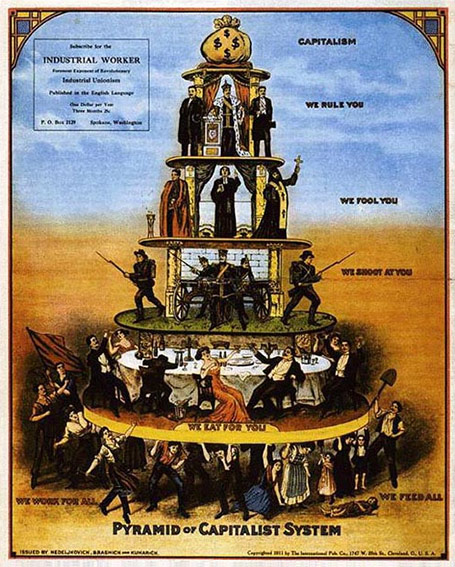

Pyramid of Capitalist System, Artist not credited, 1911

Pyramid of Capitalist System, Artist not credited, 1911

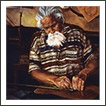

I. Trevor Walburn

The pool of steel, with its oranges and reds, all swirling slowly, glowing, and blazing—it seemed as if Carnegie had bought the Sun and employed us every day to pour a little bit of it into the converters. But there was a sunspot now on the great surface of molten pig iron. We looked down into the vat from the catwalk and it seemed to be descending farther away from me. The black spot, which many of us had stopped to look at, was undoubtedly human; I didn’t see him fall in, but after hearing the scream and upon rushing to the scene, the smell of it quickly blew past me—the smell of flesh.

No one, in fact, had seen it happen, but everyone was sure of what had. The dark blotch was curling and mixing into the rest of the liquid steel, beginning to glow yellow. Our supervisor came back and affirmed our assumptions, “We couldn’t find Clemmens, he’n’t at his controls, watchmen’sn’t seen no one leave this part, hasn’t seen Clemmens leave is what I mean to say. We’ll be sure by tomorrow.”

“We’re just as sure now,” whistled a puddler1; standing next to me, “That’s Clemmens.” He nodded with fervor and pointed at the patch of dark in the pool below us, “That’s him just down there.”

But when I looked again there was no patch of black in the melted steel. Goodbye, Clemmens. Seems as if he’ll be buried up in the frame of some building now.3

It felt silent. It didn’t fall silent, ever, but it felt silent. Our little group of watchers turned somewhat into mourners as we had this small moment of remembrance. The machines still sounded, very loudly, for they never turned off,3 and they reminded us of our duties. We dispersed back to our tasks.

The tremendous heat watered the eyes of anyone who chose to end up in this part of the works. My eyes were probably watering, but I’ve learned not to notice it, or the heat. I’ve found a much greater happiness in noticing the cooler surroundings when walking home from the mill.

Strike loomed in the smoky atmosphere. Our union contract would expire on July 1st. Carnegie was on long vacation in Scotland and it didn’t seem to me that Frick had any significant intentions to satisfy the Amalgamated.4 Well, I didn’t want a pay cut, which we were all warned of by management. Negotiations were getting nowhere either.

My house was seven blocks from the mill. As I was walking down the sixth block, I came across Clyde Grayson. He was quite the skilled worker, a tonnage man whom I came to be aquatinted with when the Lucy works merged.5

“Hello Trev,” he said to me solemnly.

He looked spiffy, much too spiffy for a stroll through Homestead.

“And what’s all this about?” I asked.

“Are you not going?” he looked perplexed at me.

I shook my head questioningly, “And where to?” but I also grew solemn as I began to realize the purpose of his attire.

Clyde let out bursts of air that I perceived to be shudders, “To the Captain’s funeral.”

I suddenly remembered, not to my happiness, “Ah…” I placed my hand on his shoulder, “Is that today?”

“Yes,” he seemed very sad over someone he didn’t know all that well.

“And where’ll that be?”

He told me it would be at the church6 and I let him go on his way.

It was true, Clyde was unusually sad for such a distant acquaintance, but I still understood why. The death of Captain Jones was a tragedy for the workers and owners alike. Our boss, he understood us and treated us with respect. He also held many patents that had proven efficient for the steel making process. Those at the top level of the company considered him a friend as well, but even worse for them, the Captain’s patents, which he still owned even after his life, were losing the company money, since they couldn’t use them anymore without the owner’s permission.7

If Jones’ death had come about by some natural cause, the overall feeling would have been a little lighter. But the end of the line for Captain Jones had come with great tragedy.

Only five days ago,8 our great taskmaster, Captain Jones, was standing on a catwalk over a blast furnace. It was a new furnace and a simple one at that. The damned piece of machinery exploded and sent our captain flying into a casting pit. He wasn’t liquefied like Clemmens, though. As I and the other men pulled him out of the coals it was a terrible sight to see. He was charred, or well done, as one fresh youngster put it, and he quickly slipped into a coma and died two days later. Jones’ burns were so horrific that some of us didn’t even know it was him who we were saving.

I entered my small house and lit a pipe that lay next to the sink. I was in no shape to smoke, but my health by now had no good prospect, so why sacrifice the enjoyment? I found my best suit and only top hat in a dusty, decaying closet and dressed for the funeral.

The sky was gloomy as it always was. I walked along the street on the right side and ahead of me could be seen the smoke stacks and the top of the mill.

II. Lewis Grant

Woodhaven, NY, a small town that held a certain prodigy for a prosperous life. Its streets that sprawled from the Avenue9 were lined with trees. The elevated train would soon be completed at Liberty Avenue. Just over a score from now, the elevated would be running straight over Jamaica Avenue and it would be connected to the various rapid transit systems of our good city.

But for now, June 20th, 1892, no massive scaffold towered over the street and my view from the diner was of the various store-fronts across from me and the blue sky.

The trolley, which a few years ago had replaced the stagecoach trolley, kept moving along as I saw my superior jump off and come into the diner. He sat across from me after his coat and hat were taken, and ordered the eggs & bacon.

“How are things at the tracks?” he said to me.

“Fine David, just fine. Not much crime around here anyway.”

“Well that’s the way you like it. You always were the lazy hands man.”

I laughed as my porridge was served. It was true what Dave said; I was noticeably indolent, a trait you wouldn’t expect from a detective. While other Pinkertons hid their faces behind tall collars and solved murders, I chose the easy route. My job as a Pinkerton Detective was simply to provide security at the Aqueduct Race Track,10 where I’d never been on duty during a robbery, riot, or murder. The biggest action I ever encountered were scuffles that always had to do with some unpaid debt.

David Craig, my captain, who I was having breakfast with, was completely opposite. His avid skill in crime solving and planning had led him to direct many high-profile cases and it was rumored that he’d be leaving the agency to open his own office. His superiority was exactly what enabled him to carry the information he was about to tell me.

“So what is it?” I prodded.

“Strike,” his eyes bulged as he said it. I knew already that he was releasing something big. Dave leaned in and spoke calmly now, his voice still boomed against the walls, “Homestead.”

“Yea,” I drew out the second question, “So what?” I thought now that he had just come by for some small talk.

“Everyone who works at the steel mill down there is part of a union, and they’ve been told of an upcoming pay-cut. They’re all going to walk out if the union demands aren’t met.”

I pondered this for a short time, “Demands won’t be met?”

“Not those of the workers.”

“Well,” I said in attempted conclusion, “What’ll they do?”

Dave smiled cleverly, “The workers call it a strike and the owners call it a lock out.”

“Thanks for the news,” I quipped, “Now I don’t have to buy a paper.”

He looked at me, then his stare wandered all over the diner. He shook his finger and nodded, “Oh yes, yes. Here’s the importance of all this.”

“Got your memory back?” I gestured for him to get on with it.

David’s eggs were served and he took a hearty portion, “The renowned Pinkerton services have been summoned… to protect the mill during lockout.”

I stared blankly and began to understand, “How many have been… ‘summoned’?”

“Three,” he paused and resumed slowly, “Three hundred.”

The most Pinkertons in one place, it seemed, were in New York, and I was likely to be one of three hundred. My shift at the races began in an hour so I covered the tab and left David at Pops Diner.11

III. Hank Walburn

The LaLance and Grosjean Factory was established by two Frenchmen well after the town of Woodhaven was itself established. But ever since the manufacturers opened shop, the small area of Woodhaven has turned itself into a factory town where many, if not most, of its citizens were employed by LaLance and Grosjean.

I was one of those citizens. My job at the factory paid well and I’d acquired a house where my wife sat happy talking to the neighbors who regularly gave us the products of their little backyard farm. I was no gentry-man, but I was satisfied.

My brother Trevor, on the other hand, was not doing well at all. We exchanged letters frequently and telegraphed every so often. From what I perceived in correspondence, Trevor’s health was depleting and the stifling hard labor at Carnegie Steel, where he worked, only added to his condition.

Of late I’d been exceedingly worried for my good brother. He’d told me of terrible casualties at the steel mill that I could only hope he wouldn’t encounter himself. Anyway, I’d asked him to come move in with me and my wife in Woodhaven. He would endure much less of a workload making pots and pans at LaLance and Grosjean. The pay, according to cost of living here, was also better. If Trevor would only move up he’d be able to enjoy a stable and good life in exchange for an honest day’s work.

But for now I did not worry, I just placed my bet and made my way towards the race. Walking into the arena, seats raising on either side of me, I noticed Lewis Grant. He was one of the many Pinkertons standing guard at the horse races and was always on duty in the section where I sat. He asked me what horse I’d placed my money on. “Dexter,” I said.

“Dexter looks good today,” he affirmed.

“Dexter!” someone exclaimed as she leaned over the wall and looked down at me, “It doesn’t matter how the horse looks, It matters how the horse runs, isn’t that right?” Her husband now leaned over also and agreed with her, “That’s right, Dexter could win, but I bet on Whalebone, he’s running much stronger lately.”

The couple’s attention went back to their own concerns and I went back to talking with Lewis. “I just bet what everyone else bet,” I said nonchalantly.

“Yea, some of those guys just make a living out of it.”

I had to laugh, “Well I spend my living on it.”

All the good seats were taken so I leaned over the railing as the horses stormed by me. I could see passed the Aqueduct—perfect squares that were houses and blocks spotted with scattered trees and large clusters of greenery.

IV. Trevor Walburn Leaves

The square was full of mill workers as the union meeting ended. We’d decided a strike would be necessary if management would insist on the pay cut and long shifts. Our AAISW leader at Homestead, Hugh O’Donnell, had strictly warned us against violence. He said he didn’t want a civil strike to turn into all-out war.

But all-out war was sure to happen. I was ready to fight with my fellow men, but good old Hugh, he knew about my failing health, and he knew I wouldn’t possibly survive the violence that absolutely would come.

He didn’t want me to have any part in the fighting. So when I received a letter from my brother in New York, who was also concerned about my health, I told Hugh. My brother had asked me to come up north and work with him at a kitchenware factory. He told me of his pleasant life, and the opportunity to lead a pleasant life myself was tempting.

But I didn’t want to leave, I felt an overwhelming sense of loyalty, and regardless of my health, I would feel guilty if I didn’t struggle with the men for a better life right here in Homestead.

Hugh gave me his blessing though, and told me that the men would feel no ill will towards me. I was given a train ticket, paid for by the union, and I’d be off to New York after work the next day.

“Andrew Carnegie takes no man’s job!12” a man next to me shouted, “That’s what he said! All he is is a rubber baron.”

“Rubber baron!” I dropped my lunch in laughter, “It’s robber baron, Irishman, it’s robber baron.”

“Well anyway,” he continued, “I can’t work this long, I’m only an eight-hour man13…”

That’s when it happened. Word had spread that Henry Frick, the manager, had ordered the services of three hundred Pinkertons to oppose a union strike. A whistle had been installed in the newest part of the mill that had only one purpose—to warn us of the arrival of strikebreakers. The strike hadn’t happened yet, but it was inevitable, and Pinkertons were inevitable too, so the alarm sounded with three sharp blasts of the new whistle.

A clerk came in from the front office and told us that a worker had canoed across the river to Union Hall and he said that the next train coming in was loaded with Pinkertons!

Me and most of the other men forgot our work and made our way to the train station. But before I went, I stopped at home and packed my suitcase.

When I arrived at the station, flocks of workers, more than a thousand, were already waiting. After a few hours the Baltimore and Ohio Evening Express pulled to a stop.

The conductor was bewildered when he was questioned fiercely about Pinkertons and strikebreakers. But he insisted that there were none on board, only businessmen headed for Pittsburgh. The cars were searched and it was true, the alarm was false. There were only businessmen on this train who had no concern with Carnegie Steel. Everyone cleared the tracks for the conductor and he steamed away. All the union members went home.

Except for me, I stayed. My train to New York was due in two hours. Clyde Grayson stayed behind to give me his best wishes and some of the girls from the public house came to see me off.

I boarded immediately when it arrived, and saw Homestead for the last time as it sank behind me.

If I could’ve found a telegraph in time at one of the many stops along my journey, I would have sent word to Hugh O’Donnell of what I’d seen. At one station, I saw on the Homestead bound side hundreds of Pinkerton detectives and Iron & Coal police. They undoubtedly were the group that was rumored to be coming. To my confirmation I saw them loading onto a train and as the engines started, I kept on going north, and the locomotive full of strikebreakers began its exodus towards Homestead.

V. Lewis Grant Arrives

As it turned out, I was called to Homestead. Me and three hundred other guards arrived at Bellevue station just west of Pittsburgh. From there we were transported to barges that were tugged down the river into the mill. Before we could get safely inside the walls of “Fort Frick14” we were fired upon by strikers.

The tugboat captains proved themselves courageous and trudged on. By the time we had gotten into the confines of the mill, parts of the perimeter had been broken down and used by union men to build forts.

The massive mob well outnumbered our forces. I had never joined the army, but this surely would be a battle as bloody as any soldier had fought. And what for, to protect some millionaire’s factory?

Nevertheless, I, as a sworn Pinkerton, had the duty to serve my call, and I would fight the strikers to the bitter end.

In the beginning, we seemed to have the upper hand. We were viciously warned not to step off the barges and occupy the mill, but our brave leader, Captain Heinde, was the first to step foot on the grounds.

Captain Heinde looked at the massive group of bloodthirsty strikers and stated his intentions, “We were sent here to take possession of this property and to guard it for this company… We don’t wish to shed blood, but… if you men don’t withdraw, we will mow everyone of you down…”

VI. Hank Walburn Broods

I went to the horse races the next weekend and was sorry to find that Lewis Grant was not on duty. In fact, it seemed like there were much less guards than usual.

After I lost some money on bad betting, I decided to go home; I was deeply melancholy with worry for Trevor. On the trolley I heard the driver talking with a passenger about the strike in Homestead. Good Lord! That was where my brother worked. He hadn’t replied to my request for him to come up, but I hoped that he’d at least gotten away from all that trouble. I seriously feared for his life.

The driver then went on to tell his passenger that the Pinkertons were sent down to guard the mill. So that was it then; Lewis Grant had gone down to Homestead. I found it humorous that my friend Lewis and my brother Trevor were on opposite sides of this mess, and that they were probably fighting against each other right now. But I also shuddered at the thought. Were Trevor to be injured in the great battle of Homestead, he would never recover. I hoped again that he had gotten out of town.

I left the trolley at Seventy-fifth Street15 and as I walked from the Avenue my shoes crunched against little pebbles between the gray stones of the road. I went along towards my house. Trees covered me overhead. It was quite cool but I sweated with nervousness over the danger my brother was in.

Every time I came home it looked the same. The house was a two story rectangular prism that went much deeper than it was wide. In the alley between my house and the house on the left were the garbage cans. And in front of the newly painted panels, a small rock garden with two trees and a stone fence came three feet out into the sidewalk.

But today my house did not look the same, for standing on the steps that lead towards the front door was a man wearing a long coat and brown derby hat. I approached him and was about to ask what was his business here, when he turned around, and to my surprise, there stood my brother.