Third Prize, Narrative

Michael Youmans English, City Tech

The Hands of Time

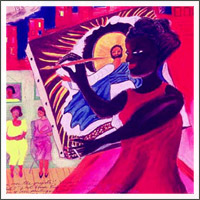

Poster from the Bread and Roses series; painting by Milton Glaser, 1980

Poster from the Bread and Roses series; painting by Milton Glaser, 1980

It was always his hands. He hated them, they were big and scarred as if they were in a constant state of pain. There were callouses on top of other callouses, as if they ran out of room to spread out and decided to built up, living on top of each other as if a small city. His fingers looked like hot dogs that fell off a bun, so badly damaged and dirty that not even the dog would try to eat. Taking one sniff would tell it that there is better prey elsewhere. He knew that if he showed her his hands it would be the last time he would see her. She would know that he was a laborer, someone who used his body, not his mind. He would then be placed in a category below, someone from another place that could never provide her with the cerebral comfort she needed.

She wondered why he kept his hands in his pockets. It was already the beginning of June and the cold winds had been replaced by a warming breeze smelling clean, fresh, with a hint of sour coming from the crab apple trees in bloom. He never held her hand, even though this was only their second date, she felt so comfortable with him already. Perhaps he didn’t like her the same way she did him.

They met in the train. She remembered the moment he walked by her, they made eye contact as he strode by—confident, silent, but forceful all at the same time. They both looked away almost as quickly as they had made contact, but it was enough. She noticed that he got on the same train car but a few doors away. She needed to get closer, so as soon as the door opened she cut to her left, looking as if she was searching for a seat—perhaps there was a map that she could look at as if she was unsure of where she was going. Having been taking the same route for over two years she smiled to herself, ‘childish’, she chastised herself, ‘but effective?’ she replied as she snaked her way to the map knowing that at least it was a bit closer. She saw him out of the corner of her eye and he looked to be attentive to her moves. They were now two benches apart, how to make up the space became apparent when someone moved to get out at the next stop and as her luck would have it, the empty space was right in front of him.

Later she found out that he was trying to do the same, not using the map as his excuse, but instead using the clumps of people who always congregate at the doors (why were they always doing that when everyone knew you were never getting anywhere fast upon exiting the train) to excuse him for walking towards her as if looking for a better place to stand. They teased each other upon discovering their shared secret.

At the same time she was devising her plan he was devising his. Perhaps he could get closer to her, but then what? He was very shy so speaking to her was out of the question. But the least he could do was to look into her beautiful eyes once before she went out of his life, so he could at least have that. A small story tucked in the recesses of the memory that he could return to when alone, deep in his own thoughts. Something to give us hope when we find ourselves in that dark place and don’t have the fortitude to feel our way back to the light. He just knew he had to have the memory if nothing else. Just then it happened, he saw her look at the empty seat in front of him, so he stood aside to block one of the Chinese women who bee-line for any empty chair, bouncing off him to pinball her way to another. Desperately seeking solace for the long ride back to whatever factory or backroom she had to work in that night. He was sorry, but didn’t care too much when she slide into her seat like a ball player sliding into home… Safe!

She saw him step aside, ‘was that for me?’ she asked herself—but she the answer was in his eyes. When she looked up into the blue that reminded her of the cool waters she used to swim in as a child. They were as deep, too, which would have frightened her under any other circumstance, but the pull was too strong for her to think about that now. No further thoughts, just take the chair. “Thank you”, was all she said—she needed an opening and here it was. She said something, now to wait for him.

Her thank you was so genuine that he answered before he could realize what he was doing, “I saw your intentions and I just thought I’d help a little bit”, he said as he smiled. They both looked over to the Asian who had claimed her post, she didn’t even notice them as she settled in for the long ride.

The gauntlet was down. Both were each smiling at their small victory when he slid into the next seat and as natural as a casual glance, they started their first conversation. It struck him how easy it was—she was like an old friend, a steamy rendezvous and a long-lost soul mate wrapped up into one beautiful package that he loved opening, one sentence at a time. He was so wrapped into their conversation that he missed his stop. He missed several more before he realized that he had long passed where he lived. They were in Bay Ridge before he even knew it, about forty blocks from his house. She stood up and said, “The next stop is mine, where do you live?”

He smiled, “We passed mine about seven stops ago. I’m in the Slope,” he answered in the local colloquialism for Park Slope. She laughed, such a captivating laugh, it reminded him his mother, her laughter stayed clear in his mind even as her features seemed to fade more and more each year. He asked her if he could walk her home, she said, “Are you sure you want to walk around Bay Ridge, being from snobby Park Slope and all.” He laughed at this; she was good, he thought. He asked her for her number on the way and they had set another date before they even got to her door. He knew that no matter how shy he was, he couldn’t just let her go without at least trying to see her again. Little did he know she was thinking the exact same thing.

“Next Saturday then,” he said as she slowly closed the door.

For the first date he wanted to take her somewhere special, so they walked near the Prospect Park Carousel, one of his favorite places in the world because it reminded him of his childhood. His father and mother, being of modest means, would take the family to the park at least once each month during the Summer so they could all ride the carousel. He felt that it was a part of him, he would sometimes just sit on the bench and watch the carousel going around and around, blurring his vision he could almost see the family as he and his brother played cowboys while his parents would coo and kiss in the bench behind. His father would always gently rub his mother’s arms as they spun around in that chair, acting as children without a care in the world. The memory of her laughter always brought tears to his eyes because it was more beautiful than the calliope music that always seemed to dim in reverence. He winced as he remembered losing them both when he was still a young man, before their time to be taken and before his time to let them go. He let the memory escape, not wanting to hold onto it this time. There was plenty of time to think about the past, but he was in the present and he didn’t want anything to cloud this perfect day.

She loved the carousel, how did he know that this part of the park was her favorite? She didn’t linger on this thought because of how right each moment was for both of them. She turned a bit as they walked and she put out her hand, perhaps he needed a little prod to tell him it was ok to hold her hand; that she wanted him to hold it.

He saw she was looking at him, smiling at him and he knew that it was only for him, that he did the right thing by bringing her here. Then he saw her turn towards him and hold her hand slightly out from her body, his eyes followed hers as they reached out to her hand as she wanted him to do with his. Oh no, please not now, was all he could think, but the only thing he could do was look dumbly at her, as if he had no idea what she wanted. She stopped and turned to him, he knew what was coming.

“Why won’t you hold my hand?” she said shyly.

“Um, er… ” he stammered. “I don’t really like to hold hands”, was all he could find to say.

Catching her off guard, she blurted, “Do you not like me?” Ready to end it here if he said so, but also knowing full well she was in for a long night of crying.

“No, no, I like you so much” he said. Calming her nerves but opening up a whole Pandora of questions in her mind. He saw the confusion in her face, so he started to tell her about his hands, but stopped. He simply took them out of his pockets and offered them to her, palms up.

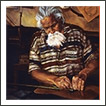

She looked at the deep crevasses in his hands, his fingers bent and swelled, looked like old lumber that has sat in the hard sun and splintered. She saw the countless callouses that had grew and regrew so many times it made his skin as hard and thick as old tires, the ripped skin like steel showing through the bald treads. She couldn’t stop staring as she felt the pain of his hands as if it was her own, her own knuckles tightened involuntarily, as her hands tightened into fists in her pockets.

“This is why I can’t hold your hand, because of these stupid things,” he said, not being able to look her in the eyes because of his shame. “They tell a horrible story of a simple man who has a simple job and who make a simple living. I want to be something more, someone more, but at an early age I fell in love with wood. I fell in love with the ability to take a rough, gnarled, ugly old tree stump and make it into a smooth, tempered, handcrafted piece of art that is priceless. But in all the years that I have made such beauty, in turn all it did was make me ugly. These splintered and damaged hands aren’t worth a ticket to ride that carousel.”

She looked at him and smiled as the tears gently rolled down her cheek. “This was it?” she asked. “This is why you wouldn’t hold my hand?” Then she began to tell him her own story, “When I was a little girl, my father would come home after working twelve hour days and he would take off his heavy jacket and work boots. My mother would never allow anyone in our house with boots on, and in that house she ruled. He would come over to the table sit down and light his pipe. Then he would sit back and look over at my sister and I, knowing what we wanted more than anything was to hear about his day. He was a stonemason and he did that his entire life, until we buried him. He was so surprised by us wanting to hear about his day, he would say that it was just like any other. There was no way we would ever let him off the hook that easily, so he would wait until we begged enough and tell us all about the other men he worked with, how the boss was always yelling things like, ‘get back to work, we are too far behind for you to have another break’ and always getting on them about not working fast or hard enough.”

She stopped and took his hands into hers. He could barely feel her softness, as he tried to pull away. She pulled back until he stopped. Defeated, all he could do was into her beautiful eyes. Which was all the comfort he needed.

“Do you know what I used to do while he told me his stories every day?” she asked.

He just shook his head silently, never taking his eyes off of hers.

“I used to look at his hands. They were like these,” she raised his hand for him to look, “You might think they are horrible, but I think they are beautiful. I loved my father’s hands because they told me stories that he couldn’t. They told me of the time when he burned himself because the lye from the cement wedged between his fingers and he couldn’t wash them for hours because he had to carry several tons of cement from the trucks to the foundation. Back and forth he would walk, making the same trip over and over, leaving a bloodied stamp on each block he carried. When he got home he could barely move his fingers, I remember my mother crying as she massaged cooling salve onto his rough, bloody palms. All he did was joke and say, ‘it’s ok, there’s ten of them, that’s plenty in case I lose one or two’, and he would calmly sit until she was done crying and still he would put us to bed, carrying us in his big strong hands like he didn’t have a care in the world. My father always told me that no one should be ashamed of what they do, as long as they do it the best they can.”

She continued, “My mother loved his hands, she would laugh at them, cry over them, yell at him to use some stupid lotion she would buy that, ‘would make them soft again’ she would say to him. He knew that they would never be soft again and so did she, but that didn’t stop her from trying and it didn’t stop him from teasing her about it. Some nights she would just sit on the couch and massage his hands, knowing that it was those hands that fed us, clothed us and gave our home to live in. I miss him a lot,” she said as our eyes locked together, “I miss his smell, his skin, his voice, his stories, but mostly I miss those hands. That was our security blanket, those hands would never—did not ever—let anything bad happen to us.”

She held his hands tightly as she pressed them into her chest, her fingers intertwined with his. She then brought them to her soft lips and she softly kissed his rough knuckles with the utmost care, “These hands tell the story of you, who you are and how hard you work, even how honest you are as a man. They tell your story as my father’s did, they tell of pain and hard work, devotion and artistic expression. Hands like yours—like his—they can’t lie, even if they tried.” She hesitated a moment as her eyes bore into his as she made her point, “They also tell me that you will be there for me, that you will care for me and that you will never let anyone hurt me.”

He smiled at her, and in that instant he knew that he had to remember every word, every syllable that was said this day, since he would be telling this story to his children. To their children.