Second Prize, Fiction

Jaroslav Eliah Sykora Math, NYC College of Technology

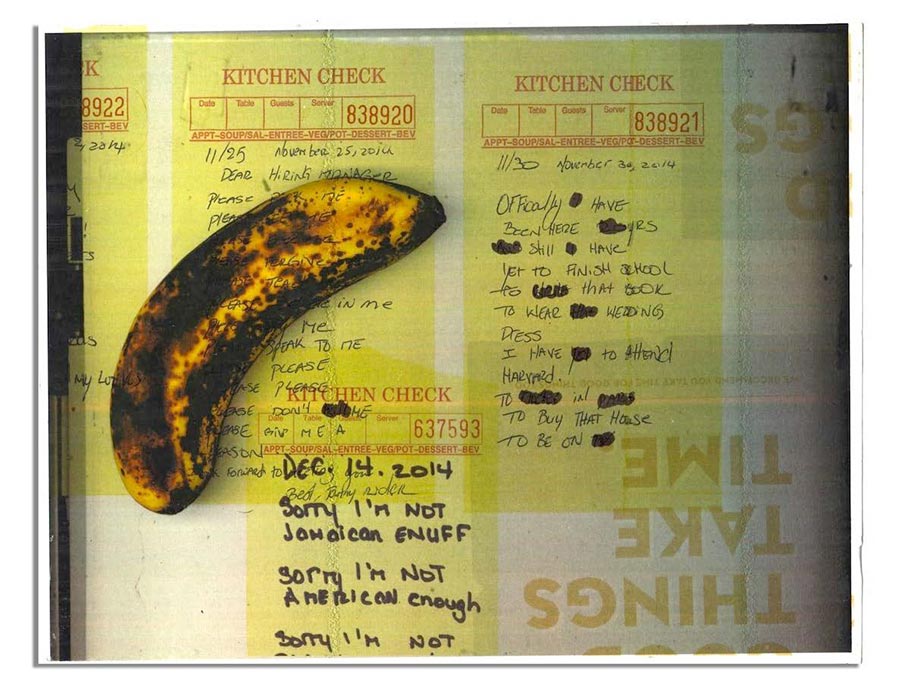

Cheechmoonda

Cheechmoonda, Jaroslav Eliah Sykora, February 2016

Cheechmoonda, Jaroslav Eliah Sykora, February 2016

“That’s the house!” Jerry parked his yellow Mercedes with his firm logo of Bernezie’s Glass in front of 12677 Stuyvesant Avenue, switched off the radio, and opened his notebook. It was a thick diary in a black cover with a strap and a buckle. The corners of the diary, unprotected with any metal shields, suffered damage as Jerry wore it on his back tucked in his weight lifting belt. Bent in a shape of a bread roll the diary looks like the pages might fall apart the moment he opens it. But they held firm in the binding although Jerry stuck his nose into it at least thirty times a day. Jerry put the notebook on the wheel and licked his thumb and index finger before he opened it in the middle. He browsed to the last two pages, leaned his elbows upon the wheel and bent over. Both pages, the left and the right, were densely filled with dates, names, and addressees of customers whom he had arranged to come to and do the job they requested. He drew his brows together, and a brief moment of concentration filled the space in the cabin of the truck. After some twenty seconds, satisfied with what he found, he closed the notebook again. “So much to do!” he sighed. “John, I can’t stay longer than one hour here. I got more work to finish this afternoon. I really have to hurry up.” He did not move his head when he was talking.

Whomever Jerry had in his truck, may it be Timmy, Gene, Kien, Oozie, or me, he never used the plural form in his verbs. It was only he who did the work, not us. Although we were his helpers whom he was dependent on, his collaborators and team members, he never included us into his diction. In his verbalism it was he who did the work, from the start till the end, from the initial call of the customer till the last minute when the work was done and we were leaving the working place. In his business vocabulary we didn’t exist, we were him.

Jerry headed out of the truck not bothering to tell me a word either about the work we came to do or what tools he wanted me to take out from the truck. He somehow expected that I would figure it out by myself. But I usually didn’t, and then he got mad. I learned I had to squeeze it out of him. “What do you want me to make ready for you, adoni?” I asked. He turned his head to me, bewildered.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” He never heard me address him that way before. His Hebrew that he’d learned more than thirty years ago at the Solomon Schechter Institute was rusty.

“It means ‘my master’”. His bewilderment faded.

“Take the usual stuff—my pouch, garbage bin, two drill guns—the second for you, the bag with the insulation, the four-foot ladder, the caulk gun, two bronze caulks, the paper roll, the compressor and the baby-nailer. Leave it in the hallway on the first floor. You’ll work on the second screwing the window brackets to the frame and installing the blinds.” He jumped out, locked the car door on his side and rushed to the house to ring the doorbell.

After some two minutes a heavy African-American woman in her early sixties opened the door. She had a round face and her curly, bushy hair was slicked backwards. The upper part of her face was covered with a pair of big square glasses sitting on her broad nasal bridge which made her look sophisticated and learned. She was dressed in a dark blue cotton T-shirt and yoga pants with a silver contour waistband.

“Hello, Mother,” Jerry greeted her loudly. “How are you today? Ready for me?”

“Hi, Bernezie,” she answered. “Of course, I’m ready for you, of course. I’ve been awaiting you like a doe longing for water streams. You’ve not showed up for ten days, bro. Come in. Hopefully you finish the work today, do you? I can’t wait any longer for you to have it done—am losing money on the rent every day, Bernezie. You hear me? Every single day!” She fought to control her voice and sound casual, but she was too upset to hide her emotions.

“Calm down, Mother. I’ll finish everything today. Promise. I’ve been so busy and tired all the time, couldn’t come earlier, just couldn’t. Tell you later. I’m really sorry about that!” Jerry whispered apologetically. His voice was humble and weak.

“If you finish it today, that’s fine,” said the woman forgivingly. “Come in.” Jerry and the homeowner disappeared inside of the house leaving me outdoors. I unlocked the side door of the truck, took the tools out and one by one lay them behind the fencing. Then I closed the side door, locked it, went around the truck and checked whether the other two doors were locked. I didn’t hurry after Jerry, instead, I let my eyes feast on the nicely structured design of the brown façade of the house. It was a four-apartment residence set into a row of historic brownstone buildings. It had all the classical features that characterize that architectonical style—rusticated pilasters, lintel stones above the windows, the three-part entablature, and the cornice sitting on the walls like a royal crown on the head of Queen Victoria. More than a hundred years ago Bed-Stuy was a neighborhood of middle and upper class inhabitants. Despite the major change of homeowners in the thirties of the past century, when the white rich people left and the poor blacks from Harlem moved in, many houses, including 12677 Stuyvesant Avenue, retained the memory of the time when those residences had been built.

Jerry appeared in the door again. “Why are you wasting my time, John? How long should I have been waiting in the hallway for the tools? Why haven’t you made them ready yet?” He wasn’t angry, just impatient as he often was when he was under stress and pressure. Then he saw the pouch with the tools at his feet, grabbed it and vanished into the house again. I followed him.

The interior bore recognizable traces of the opulent style of the Victorian gothic which the new occupants didn’t manage to preserve in its original shape. The ornate dark woodwork of the wall with the trefoil ornaments was scratched, and the molding with hand carved roses was twisted as a result of excessive humidity. The craftsmanship of the décor suffered a hard blow of time which made me feel sorry for the house as if it was a decaying living organism.

I brought the tools inside, placed them in the hallway, took my drill gun with one hand and the ladder with the other, and went up into the apartment on the second floor remembering Jerry to have said that the brackets and the blinds had to be installed in the living room only. I got up and felt the deteriorated lumber under my feet squeaking with my every step. The mahogany door was open. The homeowner claimed that the apartment wasn’t rented out yet but somebody obviously occupied it. There was a sofa- bed in the living room, a coffee table, a Samsung 65” plasma TV, a DVD-player, and a letter-format picture of Jesus Christ framed in gold on the top shelf above the fireplace.

It took me two minutes to set up my tools.

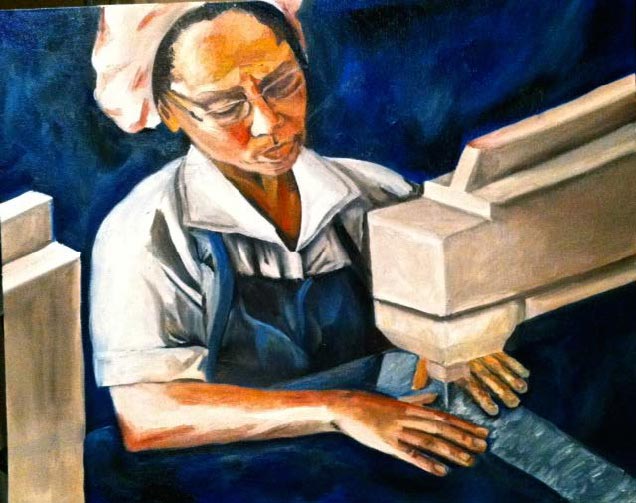

I was working alone there and I enjoyed it. I felt I did something creative, a piece of work that had a beginning and an end. For a moment I stopped being a cheechmoonda, Jerry’s unskilled helper, required only to pay attention to his commands and be ready to hold, pass, take away, bring, put, lay down, press, fill, close, open, pitch, and turn around whenever he commanded. He worked in the living room downstairs, and I was free, out of his reach, and with a task to accomplish. And to make myself even happier, I put headphones on my ears and listened to the BBC news to learn the latest about the presidential debate between Donald Trump and Ben Carson. My happiness, though, didn’t last too long. An intruder broke into it and the bubble of freedom burst. The daughter of the homeowner came in. I took notice of her not earlier than when she was already standing in the doorway.

“Hi, what are ya doing here?” she asked. Her voice was deep and strident.

“Hello, Miss. I’m Bernezie’s helper, finishing the windows. They didn’t tell you?”

“Nope, mom hasn’t told me ya’d come today. What’s your name?”

“John. And yours?” There was a pause before she answered.

“Alice.”

“Hi, Alice. Nice to meet you.”

“Ya too,” she said. “I’ll stay here and watch ya.” She plunked herself down onto the soft cushions of the sofa-bed and breathing heavily she folded her arms. She was much bigger than her mother. And shorter. She wore the same outfit as her mom, only the contour waistband wasn’t silver but gold. She had a girlish face but she certainly was in her late thirties. A set of meticulously braided ponytails with ladybug-clips made her look younger but the effect of it was weird. It looked as if she refused to become a grown- up and was suppressing her biological growth and maturity masking it with her hairstyle. She had a strong bull-neck and stiff curly hairs on her chin—the indication of a higher baseline level of testosterone in her ovaries. It gave her girlish face a masculine appearance and an unattractive look. I wondered if she ever had sexual intercourse.

I picked up the first bracket and two screws from the floor, tucked the drill gun in my belt, climbed up on the ladder, and attached the bracket to the frame. There was a massive chunk of caulk in the corner making it impossible to pin the bracket squared. I fought with my balance a bit too; the wobbling ladder made my stand dangerous, and the drill-bit was sliding off the screw-head. Alice watched me ardently wheezing as she breathed. My fight excited her so much that she began to sweat. I searched for a razor blade in my front pockets and accidentally touched my testicles. Alice’s aroused breath grew stronger. The sour odor of her sweating body filled the front of the room and hit my nose. It made me nervous. I didn’t find the razor blade so I quickly pinned the bracket askew and climbed down the ladder.

“Hallelujah!” Alice seeing that as a success exclaimed so loud that she scared me. I turned to her with reproach. Tiny silver drops popped out on her forehead and her dark eyes covered shiny foil of moisture. With one of her hands she was pressing her breasts and with the other she was rubbing her lap. She pulled her hand quickly away seeing my disconcerted face. I quickly pinned the second bracket to the frame and in the corners of the room I searched for the blind. Alice noticed my helpless effort.

“What are ya looking for, Johnny?” She changed the position of the laryngeal cartilage which raised her voice pitch a fourth. She sounded much softer and warmer than when she came in.

“Sweetheart, do you happen to know where they put the window blind?”

“There it is, honey!” She pointed at the blind thrown behind the sofa-bed. Buried in cushions she struggled to turn her body around. The blind was wrapped up in a bundle. I picked it up. “Thank ya, Jesus,” I heard her whisper. The blind was a piece of junk. Jerry called it shit, fake, garbage, and proof of American superficiality. It looked nice but worked bad. The unpainted wood shades were kept in their natural hue and made people feel comfortable but because they lay untied on the threads only, they tended to slip free no matter how cautiously they were treated. I unfolded the bundle and rolled it up. At that moment the rows of shades tore apart.

“Damn!” I cursed loudly. The shades collapsed like a tower built of cards, and rattling, fell on the wooden floor.

“Grrr,” Alice grunted from the sofa-bed. I raised the relic of the blind and climbed up on the ladder. Alice’s growl gave me a kick. I put the ends into the brackets and locked the blind. Done! Then I picked up the shades and placed them on the ladder to have them ready for drawing them back through the threads. I drew the first shade on the bottom of the blind. It was slow and patient work to put the shades back in their place. I did the second, third, and fourth. With each returned shade, Alice’s breath grew louder. I didn’t dare to turn my head. I cared only for the shades. I did the fifth, sixth, and seventh. Alice’s nasal wheeze vibrated in slow intervals. I did the eights, ninth, and tenth. Alice opened her mouth and moaned. I did the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth. Alice screamed with a suppressed voice breathing heavily. I did the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth. There was but one shade left on the ladder. I took it with hesitation and drew it slowly through the threads. The intervals of Alice’s screaming voice increasingly intensified. I waited some ten seconds longer until I heard Alice’s joyful cry-out: “God is good, yes, he is, all the time! Yes, he is, all the time, all the time, all the time!”

I was staring through the open shades of the window at the row of old oaks running along the sidewalk. The street was empty, only some teenage boy dressed in PUMA hoodie and black saggy pants stood at the intersection intensely examining cars approaching his spot from left and right. The afternoon sun was still strong and cut into my eyes with sharp beams. Instantly a set of rainbow-colored blotches blinded me, and the solid contours of the trees, buildings, cars, and the teenage boy turned into a blurred canvas of a Homer Winslow-like water-color. Suddenly a new sixty-five thousand silver Ferrari appeared on the road and stopped at the boy. The window-glass rolled down and a dark hand with gold bracelet slid out. The boy put several hundred-dollar bills in the opened palm and took from it two glassine envelopes of heroin. The boy pulled the hood over his head and rushed away from the scene. The Ferrari, in a flash of a light, accelerated and continued in its ride down the street. The whole trade didn’t last longer than fifteen seconds. I felt like I was cast in some creepy movie. A woman masturbating behind my back while I was installing window blinds, and a drug-dealer distributing heroin freely on the street in the day-light. I wondered what comes next.

I packed all my tools, took the ladder and the drill into my other hand, left the room, and went down the stairs. “I’m done!” I shouted at Jerry who worked in the living room.

“Me too,” he shouted back. “Take the compressor and the baby-nailer and get your stuff back into the truck and wait for me. I’ll be there in a minute.”

In ten minutes he appeared in the car. He sat heavily on the seat and threw his notebook on the dashboard. His eyes gleamed with relief, happiness, and satisfaction. “Do you want to hear how much cabbage I made for this job I’ve just done?” I shrugged my shoulders. ”Eighty five hundred bucks.”

“Good for you!” You deserve it,” I said with a light tone of irony emphasizing the pronouns. “You toiled for that woman like a beast!“ He noticed the ironic color in my voice but wasn’t sure if the emphasis was just the result of my Slavic accent stressing the first syllables of any word, so he preferred to just change the subject.

“And with you, everything all right?” I told him about Alice. He looked at me sternly examining my expression for a while before he asked, “Did you screw her?”

I shook my head. “She wasn’t exactly my cup of coffee.”

“Good. Never do that. Remember: Don’t shit where you eat. Never mix up sex and business. You came to her to satisfy her needs with work and get her money. If you screw your customer, she may give you less or nothing. Got it, Professor?” I nodded. “Of course, you did. You have a PhD.” He grinned cheerfully at me, pulled his car onto the road, and off he drove his Bernezie’s Glass truck to finish another job.